Those who have to take only a semester would be the equivalent of the “advanced placement” students elsewhere, while those who have to take a full year are likely the ones who find it more difficult.

Even I could get an A although I couldn’t get into Yale ![]()

In one of the linked YDN articles, they say that they changed the way they did honors qualifications in 1988 to be a percentage of the class, 5%, 15% and 30%. But I swear that when I graduated in 1990, I was told they did honors based on the number of As/A-s, so to get summa you needed essentially all As, to get cum laude, you needed half or something (I don’t remember the actual numbers)…maybe that was what it was before 1988? Or maybe they changed the rules in 1988 but they were actually effective until the class that entered that year was graduating…I remember John Blum (history teacher) saying that grade inflation (the “gentleman’s C”) started during the Vietnam War era bc if students didn’t get a C, they would lose their deferment? Hence more As and Bs at that time – no idea if this is really true, maybe he was wrong, or maybe my memory fails me…

I graduated early 80’s and my recollection was latin honors were based on percentage of class but I could be mistaken. Our suite had a summa, a magna and a cum laude – we were kind of the stealth nerds. I forget the exact GPA’s but the cum laude was around a 3.5, the magna a 3.7/3.8 and the summa around a 3.9. My S graduated a couple of years ago with a 3.75 in Econ and did not make latin honors. I was a bt shocked by the grade inflation at that time.

Grade inflation is significantly less in Quebec than the US and also Ontario. In my kid’s h.s. graduating class, the top average was 94%; only 2 students maintained 90+ across 5 years. In Quebec’s top English CEGEP (2 year mandatory college between Grade 11 and university), which sends students to Harvard and other Ivies every year, the top average for the social science/liberal arts stream was 94%. However, the Harvard lawsuit showed that the grade deflation is taken into account, with 10% added to averages coming out of Quebec before calculating student academic index.

This is what I remember at an Ivy in the mid eighties.

I graduated cum laude with just at or under a 3.5, I think, though I don’t remember seeing my numerical gpa calculated until I applied to law school years later and there was a form that summarized my undergraduate numbers. So maybe I just didn’t understand how it was done. Maybe this lack of initiative shows why I didn’t graduate magna…

Yes, the percentage scheme is common, e.g., at Columbia it’s 5/10/10.

So someone summa cum laude was in the top 5% of their class (by GPA).

ΦBK is approx. top 10%, and if awarded early (in November) then about top 2% - however “…Academic achievement is measured by strength and rigor of program as well as by grades and faculty recommendations.”

I am not sure more people are able to demonstrate advanced verbal skills. I think more people are able to demonstrate adequate verbal skills sufficient to get a passing grade.

In the math/quantitative courses, it is often necessary to have a strong foundation in prerequisite skills or passing the course is a huge challenge. So it becomes more a situation of a student can do it or they can’t. The latter must either back up a few steps and learn whatever they missed at earlier levels or switch career goals.

In contrast, a student may lack top-notch thinking, analysis, and writing skills, but still patch together enough to squeak by because the skills do not scaffold in the same way as math.

The same thing happened in HS. Grades were so inflated that it would be hard to detect extremely good students from diligent ones. The SATs were adjusted twice over the years (@ucbalumnus knows more about this than I) so that there was compression at the top of both grades and SAT scores. This meant that admissions committees had to look for more indications of particular strength than were available from GPAs/SATs. It also probably means that the elite schools get a bunch of very diligent but not exceptional students because they can’t distinguish them from the intellectually superior ones.

That clearly is happening now in college GPAs. Have the GREs and LSATs or equivalent also been adjusted to make it easier to get high scores and make it harder to discriminate between the good, the very good and the excellent?

My experience in school but especially watching my kids was that most schools do not actually teach writing proactively but seem to teach it by osmosis. You read a book, write a paper, get a grade, get back a marked up copy of the paper but probably have had to move on to the next book before you can take in much from the markup. Somehow, you were supposed to just figure out how to write from courses like this. ShawD attended a very good private HS where one of the teachers went into detail on how to write a good essay. That course was a full year, if I recall. ShawSon went to a very good public HS where they didn’t teach writing at all (which was a problem because he is both incredibly gifted and severely dyslexic). I ended up teaching him how to write. I learned how to write not in public school nor in an Ivy undergrad but in grad school, when one of my PhD thesis advisors ripped apart the first chapter or two chapters of my thesis repeatedly until I wrote the way he did (which was very good).

Unlike the essentially passive teaching of writing, teachers to try to teach math. There is the kind of utilitarian math, starting with algebra and geometry, that is critical for engineers. Then there is the really logical and more theoretical side of math, where one learns to reason from premises to conclusions in a structured way. In some sense, that is taught in HS geometry (if taught right), in classes after calculus, and in number theory.

Whether math or writing is harder to learn is both student dependent and culture dependent. I think American society has for years told girls they aren’t good at math (or that it is boring or something they shouldn’t be working on). I know a very highly selective graduate program in data science/computational and mathematical engineering. One year, it had fourteen males and two females. But, there was a much less difficult MS in statistics that students could get into or drop down from the more selective program (and I think both of the females dropped to the less selective program). The less selective program (still hard to get into) was 50/50 male/female. The males were geographically distributed. But of the females all but one (a Hungarian woman), the female half was all Asian. About half were from mainland China or Korea and the other half were Chinese-American, Korean-American and maybe a couple of Asian-American ethnicities. That program, while significantly less difficult, would still enable its graduates to enter fairly highly paid jobs. Somehow, young Caucasian women were either not applying or not getting in (I’d guess the former more than the latter) while Asian families were telling their daughters, you can do this.

One irony: it seems grade inflation is much higher at highly selective schools.

The students already receiving the advantage of an “elite” name on their diploma also receive the benefit of appearing to be top scholars.

Reported average GPA at Harvard is 3.8. At my child’s public institution that admits 80%, the average GPA of students who actually graduate is 3.43. It could be argued that it means more to be a student with a tippy top GPA at my child’s school than at Harvard.

People like to claim that the rigor at the Harvards of the world is much greater, but if nearly everyone earns an A regardless of their relative performance in a course, what have they learned and did they really benefit from supposed rigor? When an Honors College student at a state school earns a top grade that is genuinely handed out to no more than 10% of the class, isn’t that perhaps a more meaningful distinction than is generally appreciated?

Except the student pools at both schools are not the same. It is highly likely that a larger percentage of Harvard students are doing higher quality work.

I am not saying the current percentages are what they should be necessarily, just that I would not expect them to be identical.

That’s why I pointed to the top students at the state school, not the student body as a whole. Top performers in an Honors College at a state school have similar profiles to students at highly selective schools.

For those top performers, it may be more meaningful to earn a high GPA at a school where A grades are not given out as freely and there is less pressure toward grade inflation. Or, conversely, it may be less significant if that top performer happens to have a lower GPA than their Harvard counterpart. And that probably is not acknowledged by recruiters or grad schools.

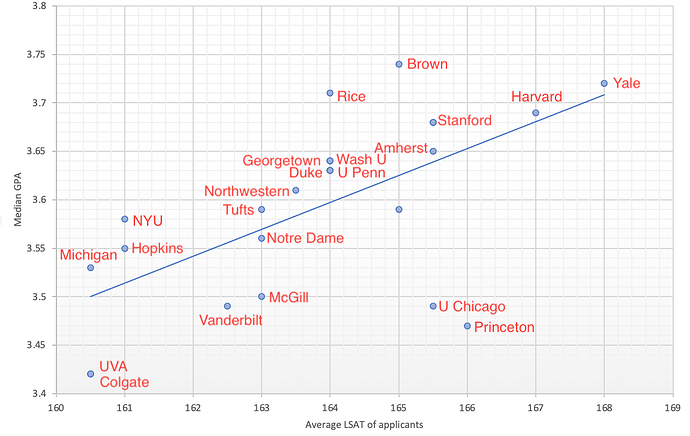

This is the correlation between GPA and LSAT score from 2015 and 2017 based on all students from these schools that applied to law school in those years. Students from schools with higher GPA’s also got higher LSAT’s suggesting it is the quality of the average student that is driving both the GPA and the LSAT score. The proximity of most schools to the line indicates that most schools use similar standards of academic excellence for awarding grades, with those notably above the line having grade inflation relative to other institutions, and those notably below the line having grade deflation. The obvious outliers are not Harvard and Yale, which land on the line, but Princeton, which was practicing university-mandated grade deflation at the time, and Brown, where the policy of allowing students to switch to P/F after getting their grade ensures inflation. (U Chicago, UVA and Colgate also have more grade deflation than expected, while Rice has more grade inflation.)

Grades are higher now than they were in 2015 and 2017 everywhere. However, it is very likely that while the intercept changed, the slope remained the same.

This topic was automatically closed 180 days after the last reply. If you’d like to reply, please flag the thread for moderator attention.