Ahh, you’ve just told me that you live in a more progressive part of the country.

The short answer to your question is no, that’s not how it is in most of the country. I live in a blue dot in a very red state and there are limited numbers of Pk-4 spots for families with low economic means and/or kids with special education needs (I’m guessing less than 1k). Public schools can offer “tuition” Pre-K (about $4500/school year) which is a bargain in comparison with private Pre-K, but there are probably less than 150-200 of those “tuition” slots available. This is in a city where there are approximately 45k K-12 students.

To give a bit more of a national picture on universal pre-k, here are some additional resources you may want to check out:

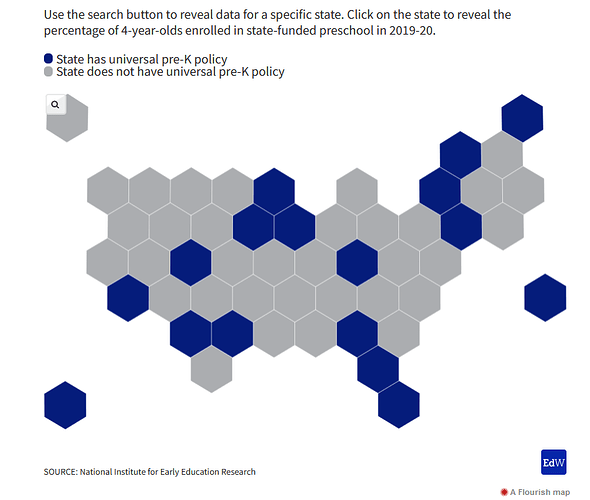

This map comes from an EdWeek article that goes into more explanation (like, don’t think that all the blue dots on this map means everyone living in the area can actually access public pre-K)

From the National Institute of Early Education Research:

State examples help clarify the variations in definition and intent to implement. At present, only in Vermont; Washington, DC; and Florida can pre-K be considered fully universal, in the sense that every child can enroll and virtually all do, though in Florida, Head Start offers such a superior service that many families choose that over the state’s pre-K program. Oklahoma offers UPK in all but a few districts. West Virginia has been in the process of expansion, but may have reached ‘universal’ in 2015. Enrollment in these states varies from 99 percent, to as low as 70 percent in West Virginia which is still expanding (Barnett, Carolan, Squires, Clarke Brown, & Horowitz, 2015).

Five states–Georgia, Illinois (Preschool for All), Iowa, New York, and Wisconsin have policies that they and others call UPK for 4-year-olds, but which fall short of allowing all children to be served. Wisconsin is the only state with a specific constitutional provision for 4K, and will fund school districts to serve all children but does not require all districts to participate. Although the policy is quite similar to that in Oklahoma, fewer districts participate and enrollment remains considerably lower at 66 percent. In Georgia, enrollment is limited by the amount of funding available year to year, and enrollment has plateaued at about 60 percent. Iowa similarly serves about 60 percent at age 4, but it is less clear why it does not continue to expand. In New York, limited funding restricted enrollment and continues to do so, though New York City’s push to enroll all children led to implementing long-delayed increases in state funding to allow for expansion. Enrollment in New York is expected to reach 50% percent in 2015. Illinois is the most egregious example of the gap between intent or ambition and implementation. Designed to serve all 3- and 4-year-olds, the program has never enrolled even a third of age-eligible children. Illinois prioritizes low-income families for services, and currently serves just 27 percent at age four and 19 percent at age three (Barnett et al., 2014)

Finally, two states have unique policies that could be considered UPK of a sort. In California, Transitional K (TK) serves children who turn five between September 2 and December 2 of the school year. As these children then attend kindergarten the following year, TK is effectively pre-K. TK is available to all children who meet the age cutoff. In New Jersey, a state Supreme Court order mandated universal pre-K in 31 high poverty districts serving about one-quarter of the state’s children. Within these districts the only eligibility criteria are residency and age–enrollment varies by district but ranges from 80 percent to 100 percent.