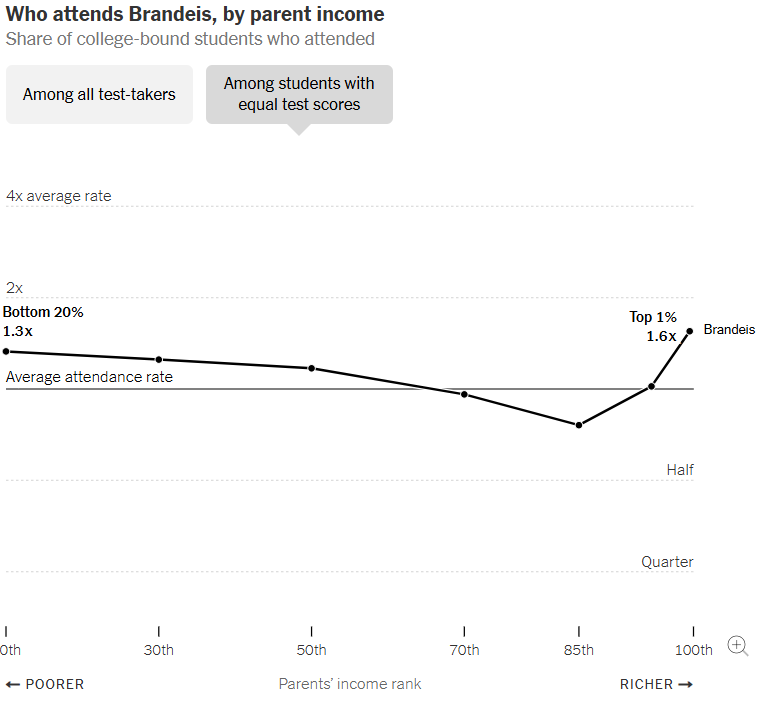

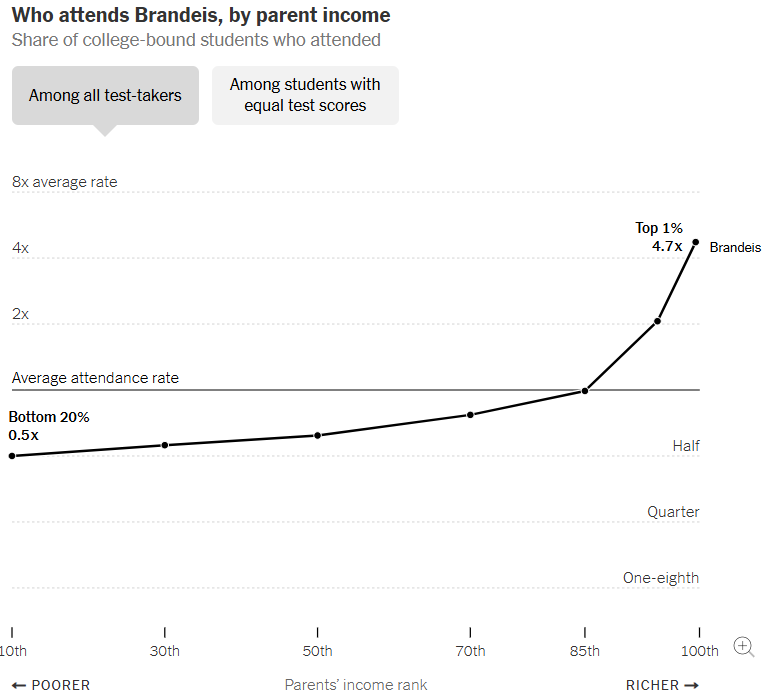

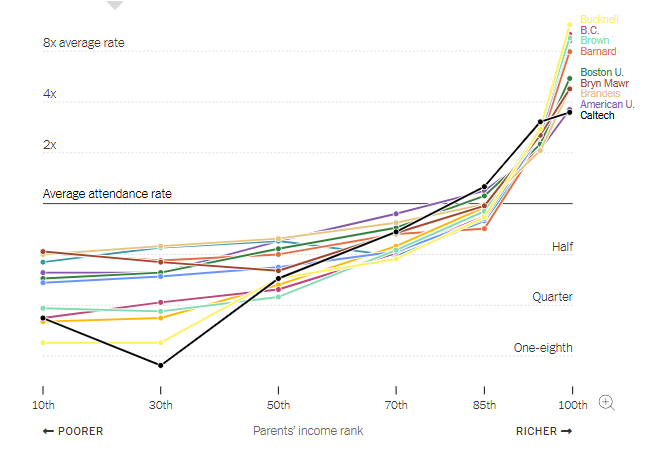

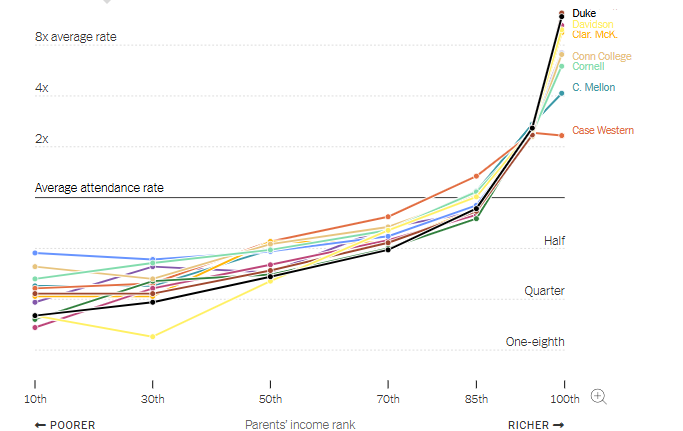

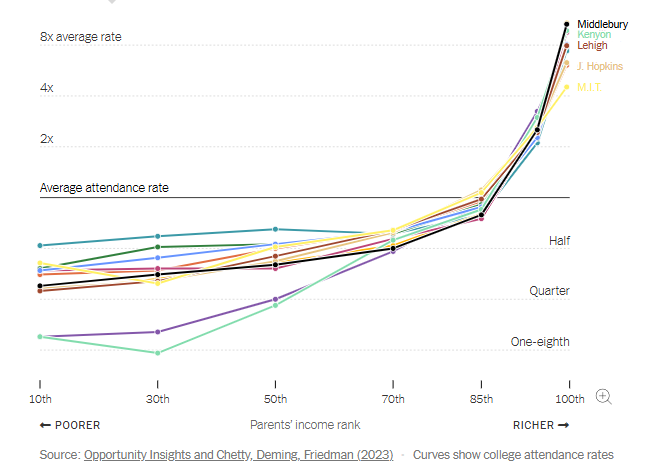

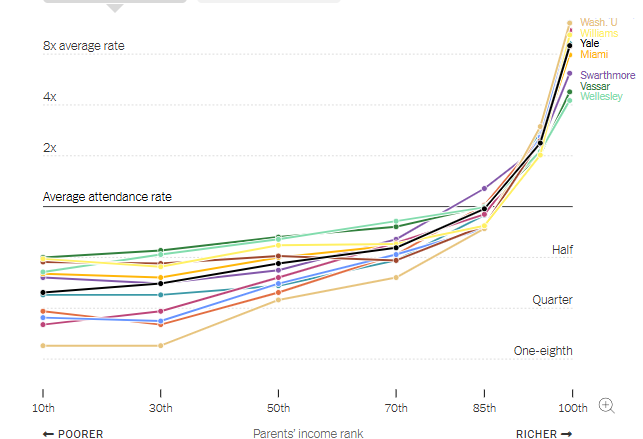

So at least as of the time of that study the NYT is relying on, this was not happening, as indicated by the graphs. Adjusting between time periods is tricky, but $200K of household income in 2024 was about 85th, $600K just shy of 99th. That was the “blade” of the hockey stick, meaning Harvard, these LACs, and so on were typically enrolling disproportionately large, not small, percentages from those income ranges.

Like here is Oberlin, say:

At that time, at least, no obvious problem enrolling in the 85 and up range.

I am not aware of a similar study conducted with data from the last few years, so possibly things have changed. But that said, in terms of anecdotes, our S24 attended a private HS with a lot of families in that range, and many ended up sending their kids full pay to privates–including us. Not that no one chases merit or goes in-state, but many do not end up making one of those choices.

I don’t think this means my experience is more typical and yours more atypical. I think instead the norms around all this vary a lot in different schools, communities, states, and so on. In fact, rationally factors like the cost and nature of your in-state options should be relevant. So too maybe the degree to which, say, local housing costs mean more or less savings goes into home equity versus something like a 529. And so on.

So I live in a state where the flagships are considered very good but not like the top UCs or Michigan or Texas or such. And housing costs in our metro have been relatively modest by coastal standards. So I think it is just sort of normal in our circles for higher-income professional families to save a lot in 529s and such, and then pay that out when it comes time for college.

Again, that doesn’t mean that is the dynamic everywhere. But the question for the colleges is whether it is normal enough among enough families with enough highly competitive applicants that they still get far more such applicants than they need to enroll as many as they want.

And my two cents is even without the really detailed enrollment data, everything else we know about the current application dynamic suggests yes, they are not hurting for highly qualified applicants from higher income families.

My guess is yield likely goes down with family income because those families are more likely to have applied to and gotten offers from competing institutions. Legacies and such might cause some noise but I would guess that is the primary relationship.

But that doesn’t really matter if they get enough applicants. Like if their average yield is 25% and it is only 20% in this group, but they get so many applicants in this group that their acceptance rate for that group could be 4% at 25% yield, then they just have to make it 5% at 20% yield to enroll the same number of students from this group.