It would be more fair, but there could be logistical issues. If the class is normally one hour, the exam needs to be made for 30-40 minutes, or a special exam time of extra length needs to be scheduled. While the latter is common for final exams, it is less common for other exams.

And this might explain why untimed take home finals are more common at my S22’s school - he’s a MechE/CivE double major. I gather engineering exams are pretty much “what you know and how you can reason”.

Aside from the correlation between income and access to mental healthcare, there is another important factor, even among the relatively affluent (I would assume that any family in the top 20% by income/wealth is aware of learning disabilities and can afford to test their kid). That is - which kids are being tested?

Kids are tested for learning disabilities if their academics do not match the expectations of their parents. That means that a kid who has demonstrated that they are academically inclined in ways that doesn’t require the amount of sitting down, or doesn’t require the ability to read fast, or is very good when asked questions verbally, etc.

Parents who are more likely to have their kids tested are parents who have college degrees, and generally have careers that require reading, sitting down, etc.

So kids who are the most likely to apply to “top” colleges are also the sort of kids who are more likely to be tested for learning disabilities.

There is also another set of students who are much more likely to be diagnosed with a learning disability, regardless of their academics, and these are student-athletes. There also actually seems to be a higher prevalence of LDs among student athletes. The stigma of an LD among students athletes also seemed to have been higher, and the growth in diagnoses is the result of the weakening of this stigma.

In LACs, the percent of student athletes is pretty high, so it’s not surprising that there are so many kids with diagnosed LD at Amherst

https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2305&context=ijahsp

Of course, overdiagnosis among the wealthy is also an issue (or perhaps severe underdiagnosis among low income kids).

The thing is, the high-stakes tests at my child’s large public college account for 70-80% of their stem class grades, and my child has noticed that she is definitely at a disadvantage compared to her many, many peers with testing and registration accommodations. These are the peers they will be up against for grad/med/pa school. We were shocked with the number of students that have it, ironically, many of them coming from pricey private schools in the area. This is not to say there aren’t plenty of kids who qualify or need these accommodations, but there are most definitely wealthy families stretching the narrative to benefit their child with higher gpas and better class schedules. Out of my child’s 4 person suite freshman year, 2 had accommodations and were perfectly functioning young adults who did come from pricey high schools. My child lived with them and can attest to the functioning. They both ended with close to 4.0’s that year with plenty of time on all of their high-stakes, make-or-break-your-grade exams and all the best professors and class times because they got to register before the seniors.

There are plenty of legitimate disabilities that aren’t necessarily obvious while living with someone. My son’s disability isn’t noticeable to his roommmates.

I don’t doubt this and this is why this whole thing is such a sticky topic. Like I said, there are plenty of people that need and deserve accommodations, 100 percent. But there are also people out there taking advantage of the system.

This! Almost nobody who knows me, works with me or has lived with me, thinks I have a disability. My wife and daughter know me well enough to see it clearly (that is also in part because I have my guard down with them), and it is obvious to them, but not to most people. I even had a boss once tell me how much she loved working with me because of how organized I am compared to most people. That was so far from the truth, it was laughable to me. I have just been great at finding ways to compensate and mask the realities of my challenges. The chaos that I distill to make things appear organized outwardly is profound, and I don’t always succeed.

I imagine if I had testing accommodations in school, I would have been the person people would be posting about as “perfectly normal” and high performing and doesn’t need them (with undertones if not outright claims, that I was cheating the system with a b.s. disability). But, every timed test was a struggle for time, even the ones where most of the class was done early. I did extremely well in school, but the effort I put in, the anxiety about strategies to rush and guess at the end of tests, was outsized compared to everyone else, including everyone else who was excelling. It is only since being diagnosed as an adult, and getting treatment, that I realize how much unnecessary suffering I had for all those years that could have been avoided. Everyone read my grind as perfectionism and an insane work ethic, but it was just coping and compensating.

One of the most frustrating pieces of being high functioning with an invisible disability is that people don’t believe you, minimize its impact based on their faulty perceptions, or assume you have nefarious reasons for the supports you need.

This thread is full of comments like I’m sure “some” of these people need accommodations, but I see so many who are perfectly “normal” who are getting them, to the detriment of me or my kid. While all of us seem to acknowledge that there are “some” cheaters, many of those commenters seem to clearly believe that there is rampant cheating with the majority (or close to it) of accommodations seekers being people who do not need them who are just trying to get an edge. They suggest it is the minority of us who actually need them, based on their eyeball test of what they see and incomplete data on increases in accommodations.

I really wish some of these folks calling so many people cheaters could just spend one semester taking tests as me. I think they would understand things very differently if they could actually see what it is like to be someone who everyone thinks is really smart, but who always silently struggled to stay on top of the deadlines, not get lost for time when studying, and had to worry if he would finish (or at least come close) on every timed test, among other things. I wish they could see the effort it would take to do things they do not even think about (and frankly how little effort it actually took me to do some of the parts they think are hard).

Of course, I do not know how much cheating there actually is out there. What I am confident about though, is all these people claiming that people looking like they don’t need accommodations is actual evidence that cheating is rampant are talking nonsense. Many of us seem “normal” to most people.

Exactly.

And then make (imo offensive) judgements about who “looks normal” or not.

And by corollary, how hard it is for neurotypical parents to really understand the challenges their kids are facing. It was actually a revelation to us when the neuropsychologist carefully explained the differences. And I think back to those kids in school in my day who were just written off as difficult or lazy, and wonder how many of them would have benefited from actually being evaluated and treated/accommodated.

Same with mine. She is a master at masking her issue, and that’s kind of part of it.

As someone who has been in education for nearly 30 years, I can comfortably say that in the past 5 years, educators have gotten more comfortable stating the issues to the extent that people are listening and getting their kids assessed. Maybe it started before covid, but somehow, that illuminated issues for kids who had been coping before that. And after covid, many of us felt comfortable saying things in a way that made parents pay attention and get their kid the help they need, or see it as a positive, not a stigma.

I was incidentally just reading an email from a college counselor who specializes in learning disabilities, and interestingly one of the things she says is that some students who can benefit from accommodations don’t use them, either from a perceived stigma, the perception (as we see in some posts here) that they are trying to game the system, or often because at many colleges the process is confusing and cumbersome, especially as most or all of it has to be done by the student with parental involvement limited or not allowed. And that is sad to me. And probably also underlines that the wealthier families with better resources are more likely to be the ones whose kids benefit. (I’m not saying they shouldn’t benefit just because they have resources, but acknowledging that it further widens the gap.)

This may be tangential, but in some cases parents may not know that they can request an evaluation in the public schools to see if the student meets eligibility for accommodations/eligibility for special education services. In some cases, if the student is performing at expected level academically, even if they have created their own compensatory strategies, the need for a referral to evaluate the need for support services may potentially be overlooked. And in my experience, the private evaluations were more commonly requested by families that could afford it, since insurance is limited in what it covers and under what specific criteria. Many providers don’t accept insurance so the family has to file it themselves and it can be cumbersome/unwieldy and confusing (trust me, it is for the providers too!). Rarely (if ever) does insurance cover an evaluation for “educational purposes”, even if the child has a medical diagnosis.

On the other hand, there can be cases where a child is evaluated and the data doesn’t provide sufficient support for a diagnosis of a specific disability. This is where sometimes people feel a diagnosis could be “bought”, because frequently when parents bring a child in for an evaluation, there may be an assumption/expectation that the test results will automatically support a diagnosis, and that isn’t always the case. And back in the day, (not sure if this is still true) College Board requested a copy of the evaluation and their professionals would often review the data when testing accommodations were requested. That contributed to many more denials/reviews/appeals, etc.

When I think about the years my kid white-knuckled it through school before I really noticed (believed) something was off I could cry. The idea of test anxiety wasn’t something I trusted because I didn’t understand myself how that could really be a thing for a kid that seemed so confident. Then a teacher I had a broader relationship with pulled me aside in kid’s sophomore year and said “this isn’t typical, he’s really struggling”. We were fortunate enough to be able to afford the testing where that, along with a few other things, was diagnosed. Even then, I don’t think I really understood the impact of testing environments on him until COVID hit and he was one of the few students whose grades improved. And it was because he wasn’t in a classroom anymore, the time pressures were gone. He could simply breathe and show what he knew. Schools going test optional was the greatest gift he could receive in his college app process.

He went through the rigamarole to get his accommodations set in college. But, it’s been said in this thread before, having accommodations set by the disability office only means that the student can go professor by professor, class by class, to work out how those work in each class instance. It’s not for the faint of heart. And so he got very specific as to when he needed to do that legwork and when he didn’t (classes with 4 exams no papers vs. classes with 3 long-term projects only for instance).

All this to say, I never worried whether other kids were doing this same work, whether they needed it or not. Having that kind of time to worry about what other people are doing and if they should be or not would have been quite the luxury.

This article seems to show different patterns in the prevalence of LD among kids than what is suggested by the data about the prevalence of accommodations.

Here is another study, over a shorter period, but it also shows similar trends regarding income and education, but shows a small increase in diagnosed cases of ADHD between 2006 and 2017, but much smaller than the increase in number of kids with accommodations.

Since the kids who receive accommodations need a formal diagnosis, that means that the percent of kids with diagnoses is going up, and wealthy families have a much higher percent of kids who are diagnosed with an LD. Yet that is not what is being shown in the NIH article.

It is important to note that the NIH article is based on what people report on a survey, so we have to consider whether a person will respond to a survey and whether they will respond truthfully to the question “does your kid have a diagnosed LD?”

However, the stigma of having an LD has decreased, so this should result in an increase is the percent of kids reported to have been diagnosed with an LD, however, this did not happen. For the patterns in the NIH articles to match the patterns seen in changes in accommodations, parents would need to become far less likely to admit on a survey that their kid has a LD, while, at the same time, MORE likely to agree to have this same information known (it’s not something that can be kept secret if the kids are getting time accommodations).

So I am really not certain what is going on here.

PS. While there has been an increase in the percent of kids diagnosed with developmental disabilities, as well as the number of kids diagnosed as being ASD, the increases are far far smaller than those in percent of kids getting time accommodations.

Though the second study was specific to 10 diagnoses while 504 plans (accommodations) are developed for diagnoses far beyond those in the study.

n of 1 but my kid’s diagnoses wouldn’t have fit any of those 10 categories

As @ububumble indicated, learning disabilities are not synonymous with eligibility for accommodations.

I tried to follow some of the references in the NIH article about students identified as having learning disabilities from ‘97-’21, but was unable to find the exact terms/questions used for when families were asked if anyone had been identified with a learning disability. For those who are not aware, Specific Learning Disability (SLD) is primarily composed of dyslexia, dysgraphia, and dyscalculia. So unless a student was diagnosed with an SLD, the parent may have responded no to the question, even if their child would otherwise qualify for accommodations under IDEA.

For some reference:

Of the 15% of the U.S. school-age population who received disability services under IDEA in the 2022–2023 academic year, 32% received services for SLD as the primary disability. (source)

So there’s a lot more that qualifies for accommodations than just those who have an SLD.

94% of students with SLDs received accommodations in K-12 education, but only 17% received them in postsecondary education (source)

My guess as to the reason for that significant of a difference? Stigma avoidance.

Since we’re using the National Institutes of Health as a trusted resource, here’s another one on learning disabilities:

It shares some of the criteria to qualify for a learning disability, including:

-

Criterion B: Academic skill is substantially lower than expected when compared to standard, resulting in significant dysfunction

If a student’s performance is significantly lower than might be expected based on cognitive tests, but is not substantially lower than the grade level standard, students can end up being denied services.

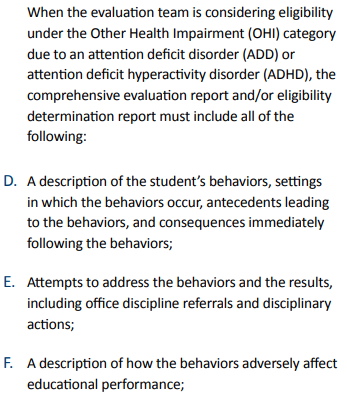

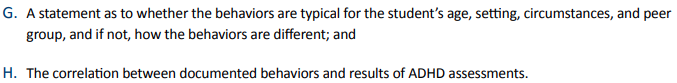

Additionally, there’s a category called Other Health Impairments (OHI) that can qualify for services under IDEA. Even when the federal government calls out specific examples of impairments (like ADD/ADHD), there are systems out there that can make it extraordinarily challenging to qualify for services. From a volume on OHI from the Mississippi Department of Education, the state is requiring that eligibility determination reports include all of the following:

If you think that it is easy to get this documentation from all teachers, disciplinarians, administrators, etc., think again, particularly at a school with too much work across too few employees.

Additionally, that same NIH article I linked shares this about comorbidities:

Learning disabilities do not often exist in isolation; rather, they present comorbidly with other learning disabilities and psychiatric conditions. The most common comorbid disorders are attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, bipolar disorder, anxiety, depression, and oppositional defiant disorder. Some studies suggest the existence of learning disabilities in 20-70% of children with psychiatric conditions.[14]

So the odds of having a learning disability are also higher for the anxious kids or ADHD kids or ASD kids. So it may not be that families are trying to game the system by getting as many “labels” as they can get attached to their child…it may just be that if a kid has one label, they’re likelier to also show the traits that qualify them for additional labels.

The Atlantic article has triggered a discussion on one of my professional listservs. Some of the discussion has digressed into learning differences vs disabilities and functional differences that can have an impact on a potential career choice, if a person cannot perform effectively independently.

Regardless of whether one has an diagnosed or theoretically diagnosable disability, wouldn’t career choice or preference for anyone be at least partially based on choosing a path that maximizes use of one’s strengths while minimizing use of one’s weaknesses, including any that may be caused by a disability?

(Of course, there are other factors like availability, opportunity, and competitiveness of any given career path.)

Which is completely irrelevant to whether or not someone qualifies for accommodations at college, but of course certain people are going to latch onto whatever they can to undermine disability accommodations. (Admittedly I’m a little prickly at the moment because I saw earlier an article from a right-wing publication basically accusing everyone who gets accommodations of cheating. Add to this the removal of more disabled-friendly fonts (war on calibri!) and wanting to take away sign language interpreters when the president speaks, it just feels like there is almost a coordinated effort here to undermine accommodations. It’s not even like disability depends on political beliefs.)

Maybe, but not necessarily. And some believe that they are able to manage their area of weakness (with or without accommodations) but then find that it is problematic. And the ADA guidelines for the work environment are somewhat different than in the educational arena. First, if the worksite has fewer than 15 employees, they don’t have to comply with ADA guidelines. If they have more than 15 employees, they have to provide “reasonable accommodations” (which may be defined/interpreted variably) and the employee has to otherwise be able to perform “the essential functions of their job”. All potentially sticky.